Credit: Greg Miller, Senior EditorFollow on Twitter

Tuesday, September 21, 2021 from American Shipper

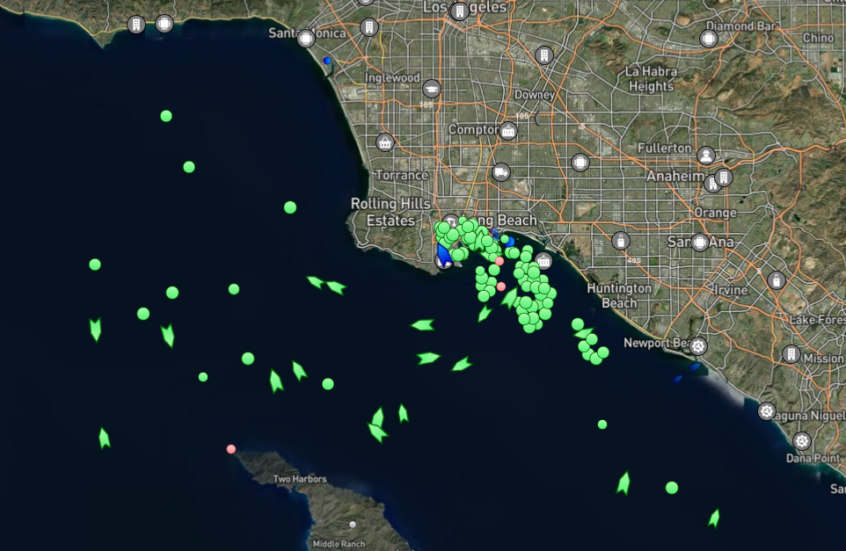

With around 70 container ships loaded with cargo now waiting at anchor or drifting off the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, how deep of a hole are the terminals actually in?

To answer that question, American Shipper analyzed data from the Marine Exchange of Southern California on exactly which ships are stuck out there.

While the numbers fluctuate from day to day, there were 70 container ships in the queue on Monday with total capacity of 432,909 twenty-foot equivalent units. To put the enormity of that number in perspective, that’s more than the inbound container volume the Port of Long Beach handled in the entire month of August. It’s roughly what Charleston handles inbound in four months and what Savannah handles in two.

The combined import throughput of both Los Angeles and Long Beach in August was 893,118 TEUs. Assuming ships waiting offshore are effectively full and capacity is a good proxy for volume, and that terminals are able to process vessels at the same pace they did in August, the anchorages and drift areas could only be completely cleared if no ships arrived for 14 days straight days.

Not only would that never happen, but there is no letup in arrivals in sight. Vessel-positioning data from MarineTraffic confirms that a steady stream of container ships remains en route across the Pacific, destined for Los Angeles.

How long ships wait for berths

The Port of Los Angeles publishes the average waiting period for a ship to reach one of its berths. On Tuesday, that number rose to an all-time high of nine days (calculated on a 30-day rolling average basis).

To gauge how much capacity has been stuck waiting for how long, American Shipper looked at aggregate TEUs by arrival date.

Thirty-six ships with a total capacity of 230,803 TEUs arrived in port waters in the seven days through Monday. That’s 54% of the total TEU capacity waiting offshore. Another 27 ships with total capacity of 176,892 TEUs arrived between one and two weeks prior to Monday, representing a further 42%. The remaining few ships arrived in late August and early September.

The ship waiting longest in the queue as of Monday, according to the Marine Exchange, was the 1,713-TEU AS Serafina, which arrived almost a month ago, on Aug. 25.

Several larger container ships have suffered waits of beyond one week. The 13,092-TEU Maersk Elba arrived Sept. 7; the 11,142-TEU MSC Avni on Sept. 9; the 11,356-TEU CMA CGM Callisto on Sept. 11; the 10,055-TEU Hyundai Neptune and 14,036-TEU MSC Livorno on Sept. 12; and the 14,026-TEU ONE Blue Jay on Sept. 13.

Arriving ships have gotten smaller

A significant change over the course of this year’s congestion crisis is that the average capacity of ships calling in Los Angeles/Long Beach has decreased, meaning that terminals handle more ships to move the same throughput.

In the current peak season, new trans-Pacific services have been introduced that use smaller vessels, pulling the average size down. The primary reason: Virtually no larger container ships have been available for sale or lease in recent months; operators are adding capacity via smaller ships by necessity, even if it means chartering them for short periods at astronomical day rates.

During the congestion peak reached earlier this year, on Feb. 1, there were 40 container ships at anchor in San Pedro Bay, which at the time seemed enormous but now seems middling. The total cargo capacity of anchored ships then was 322,721 TEUs. Of ships at anchor on Feb. 1, 15 were 10,000 TEUs or larger, or 38% of the vessel count. The average capacity in the Feb. 1 queue was 8,068 TEUs.

In contrast, as of Monday, there were 17 ships larger than 10,000 TEUs at anchor or drifting, representing only 24% of the total ship count. The average capacity of all ships in the queue was down to 6,184 TEUs — 24% below the average ship size on Feb. 1.

The change in ship size helps put the growth of the offshore queue in context. The news headlines focus on the total number of ships waiting for berths, which has risen from 40 in February to around 70 currently, an increase of 75%. Yet the aggregate capacity of ships in the offshore “parking lot” — a proxy for delayed cargo — has only risen by 34% over the same timeframe, because of the declining size of ships in the queue.